Across the great divide

by Ben Thompson, The Observer

by Ben Thompson, The Observer

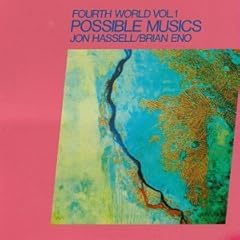

In 1980, Jon Hassell and Brian Eno released an album of woozy, African-themed ambient fragments called Possible Musics. The idea behind this strange and magical record seemed to be to try to imagine what a fusion of sounds from the northern and southern hemispheres might sound like. Twenty-eight years later, this dream is on the point of being realised.

In recent months, watching Björk's live duet with Malian kora maestro Toumani Diabaté at Hammersmith Apollo, or hearing Tony Allen's limber Nigerian polyrhythms underpinning the older, wiser, Britpop of Damon Albarn's The Good, the Bad & the Queen at the Love Music Hate Racism Carnival in Victoria Park, it's felt like those Possible Musics are in the processing of becoming a reality. And the truly remarkable thing about this new African adventure is that the main impetus for it comes not from the kind of highbrow avant-garde sources one might expect, but rather the notoriously backward-looking and insular enclave of indie rock.

When pop historians look back upon 2008, they will struggle to unearth a more momentous eventuality than the lost tribes of Camden Market finding sonic salvation in a continent traditionally regarded as beyond the pale by generations of pasty-faced Velvet Underground impersonators. For beyond the immediate excitement of indie's new African frontier - from the haute-bourgeois hi-life of this year's biggest breakthrough band, Vampire Weekend, to the wiry student Afro-beat of OMM53 cover stars, Foals - there lurks a change in our appreciation and understanding of African music so dramatic that it might almost be called a revolution.

How better to prepare for an in-depth exploration of seismic cultural shifts than with a live appearance by Hard-Fi? A year ago, the idea of these doughty Staines plodders being joined onstage by Algerian rebel-rocker Rachid Taha to perform an Arabic language version of the Cure's 'Killing An Arab' would have seemed like the stuff of a music press April Fool. But this is exactly what happened at the African Express show at the Olympia Theatre, Liverpool in March.

With more than 130 musicians fulfilling that promise so often made in live performance but so rarely fulfilled to 'play all night long' in a sequence of almost equally improbable combinations, this event was properly acclaimed as a triumph. Flushed with excitement at performing 'Take Me Out' with Baaba Maal, and a new song with Malian ngoni wizard Bassekou Kouyate, Franz Ferdinand guitarist Nick McCarthy enthused: 'Afrobeat is the new thing. Ethiopian mixes are everywhere. We're getting really into it...'

It was around this time that the canny Scots ensemble announced that their promising flirtation with Girls Aloud producer Brian Higgins was to remain unconsummated. In the quest to complete their long-awaited third album, Franz Ferdinand had opted instead to throw in their lot with the hip sound of the moment. 'Our new songs have an African feel,' McCarthy insisted. 'The whole album does.' Surely it can be only a matter of time before U2 announce their intention to record their new album in Morocco? Oh, wait a minute, that's already happened.

Readers can be forgiven a twinge of alarm at the prospect of having to listen to a generation of Anglophone rock aristocrats claiming that there has 'always been an African element to their music', but this unexpected turn of events should not be greeted too cynically. First, because - whether the bands concerned really believe it or not - there will always have been an African element to their music. Second, because, like the Vampire Weekend performance at ULU earlier this year, which only really caught alight after someone interrupted it by setting off a fire alarm (and the fact that Afro-indie éminence grise Damon Albarn was seen dropping his trousers at a security guard on the staircase shortly before this incident took place certainly didn't mean he had anything to do with it), this is one of those instances where the ringing of alarm bells actually signals that the best is yet to come.

Far from being a source of environmental anxiety, the faddishness that fuels the Afro-indie bandwagon is the basis of a positive kind of climate change. For if there is a unifying theme to the healthy aesthetic realignment that is currently under way in our understanding of African music, it's an acknowledgement - a celebration, even - of the fact that it is no more immune to the whims of fashion or the corruptions of the human ego than the sonic artistry of any other continent.

In the autumn of last year, a cluster of new bands - among them the Dirty Projectors and Yeasayer - began to irrigate the barren fields of New York's underground rock scene with the life-giving fluidity of Afrobeat. The coltish Foals were pawing the ground on this side of the Atlantic, but precocious Columbia University graduates Vampire Weekend were undisputed leaders of the pack. While this urbane Ivy League quartet's infectiously tuneful debut album was generally well-received, some of the critical responses showed just how much ground remained to be covered.

One UK national broadsheet reviewer observed regretfully that he was 'not sure if African music is as interesting as they think it is' (substitute 'American' for 'African', and imagine the band under discussion as, say, the Beatles, and the inherent absurdity of lumping a whole continent's music under a single banner in order to dismiss it as overrated rapidly becomes apparent). Q magazine began a generally favourable review with the bewilderingly callous observation that 'Africa is back on the rock'n'roll map, and for once no one's wheeling out starving toddlers covered in flies'.

How did it become socially acceptable to view African music as an exotic irrelevance and/or a tiresome reminder of the necessity for charitable giving? To make sense of this cultural aberration, it is necessary to get to grips with a historical process in which Live Aid is the end - rather than the beginning - of something beautiful, the 'world music' category gradually turns from an effective marketing strategy into a kind of wholemeal ghetto, and Live 8 is the final insult that begets a glorious new beginning.

Setting aside long-running arguments about where the blues originally came from, there are very few manifestations of modern popular music that cannot claim at least a partially African root-system. These subterranean links have a way of showing up in the most unlikely places, from the music of Nick Drake (whose classic debut album, Five Leaves Left, derived its sumptuous instrumental adornments from exiled South African jazz men) to the birth of hip hop (and the fact that Afrika Bambaataa got the idea for his Zulu Nation from watching Michael Caine in Zulu! only rendered the post-imperial complexity of this transaction more captivating).

If there was one period in pop history when African influences really came to the fore, it was amid the post-punk ferment of the late Seventies and early Eighties. While the Jon Hassell and Brian Eno collaboration may not have set the charts on fire, Eno's collaborations with David Byrne and Talking Heads combined with the buccaneering globalism of Malcolm McLaren's Duck Rock to institute a period of unprecedented cross-fertilisation that seems to have come to an end with Live Aid in 1985.

The idea that Live Aid marked the point at which the musical freshness of the early Eighties coagulated into something rather staler is implicitly addressed by Vampire Weekend. How else to explain their penchant for dropping sardonic lyrical references to Peter Gabriel and Benetton (both intrinsically - if not chronologically - 'post-Live Aid' phenomena) into music that gleefully accesses the less corporate 'pre-Live Aid' sensibilities of the Beat and Orange Juice? In comparison, the superstructure of Paul Simon's definitive 'post- Live Aid' Afro-pop crossover statement Graceland (1986) now feels as colonial as the architecture of Elvis's mansion.

The vital material succour which the proceeds from Live Aid's festival of good intentions brought to victims of famine in Ethiopia had unwelcome cultural side-effects. Not so much in Africa itself, as in the eyes of the British and American music industries, wherein it seems to have stigmatised not just Ethiopia, but the whole continent, as a place which somehow needed Queen and U2's help. If you wanted to find a single incident that summed up the regrettable contraction of musical horizons that took place in the years after Live Aid, it would probably be the moment on BBC2's Glastonbury coverage in 2003, when Jo Whiley expressed outright bewilderment at John Peel's assertion that the person he was really looking forward to seeing was Kanda Bongo Man. Over the past two decades, as the meaning of indie has mutated from Peel's conception of the word to Whiley's, its deracination from African root-systems has been virtually complete.

Nor has this just been a failing of the broadcast media. When the Melody Maker picked up the NME's discarded baton to style itself the intellectual vanguard of the British music press in the late Eighties and early Nineties, the African grounding which had been part of music's core curriculum throughout the previous decade somehow got lost in the shuffle. In the mid-late Eighties, Zimbabwe's the Bhundu Boys had been as integral a part of the teenage musical education as Billy Bragg, the Smiths or New Order. But by the time Melody Maker folded, leaving an ever more timid NME plodding on its wake, the days when it had put King Sunny Ade on its cover seemed so far off that it might has well have been a different paper.

As the indie establishment moved in one direction, the newly inaugurated 'world music' camp shifted in another. The excitement of the inaugural Womad festivals in the very early Eighties - Echo and the Bunnymen playing with the Burundi drummers, Peter Gabriel rescuing the whole noble enterprise from the brink of the fiscal abyss - had quickly coalesced into a more rigid organisational identity. And as 'world music' evolved from a record shop labelling strategy into something more like a lifestyle brand, the social and cultural baggage associated with the term was increasingly off-putting to those outside its charmed circle of pan-global righteousness.

Andy Kershaw's ominous drift from Radio 1 to Radio 3 exemplified world music's perceived shift from 'pop' to 'high' culture. The ultimate confirmation of Africa's alienation from the rock'n'roll mainstream came with Live 8, when Bob Geldof proudly - and apparently obliviously - announced the bill for a concert to raise awareness of the continent's economic situation which featured no actual Africans.

'I just thought that was insane,' remembers Ian Ashbridge, MD of Wrasse Records (home of many a competitively priced Fela Kuti reissue). The anger prompted first by Geldof's oversight and then by 'the awful apartheid corralling' of the subsequent, hastily organised 'Africans-only' sideshow at the Eden Project bore life-enhancing fruit in the form of the Africa Express coalition.

From an initial informal gathering of promoters, managers, journalists, and Damon Albarn (whose 2002 album Mali Music had been the exception that proved the rule in terms of indie indifference to the creative possibilities of an African entanglement), the germ of the Africa Express idea quickly began to ripen. Its first flowering was a riotous extended jam session in an out-of-the-way field at last year's Glastonbury. With some high profile consciousness-raising trips to Mali and Congo feeding into March's coming together in Liverpool, the harvest which might be reaped is only now beginning to become apparent.

Plans are being finalised for their most ambitious series of happenings to date: a spectacular sequence of inter-continental coups to unfold in the autumn. With the wholesale participation of Radio 1, NME, etc, guaranteed by the magnitude of the names involved, these events promise more than just a reprise of the early Eighties' happy convergence of Anglo-African musical interests. If the momentum can be kept up, they could bring African music closer to the centre of UK pop discourse than it's ever been before.

I remember going into African music heartland Stern's on the Euston Road three or four years ago - for the first time in more than a decade - and being shocked by how the atmosphere had degenerated. What was once a dynamic place to visit had become (in the course of 'world music"s shift from vibrant pop category to self-consciously worthy rump) a virtual aesthetic desert.

There was still plenty of great stuff in there, including an excellent biography of Congolese pop giant Franco, which recounted the way he used to eat an entire goat in front of his band without sharing it, just to show them who was boss (it is a little-known fact from the early days of Britpop that Damon Albarn used to do the same thing to Blur). The problem lay with the visual presentation: the prominent display of those horrible Putamayo world music compilations being a case in point. It's no accident that this series sounds like an imaginary Hispanic swear word: have you seen the covers they put on those things?

But venturing back to Stern's in 2008, the sensitive modern shopper can be assured of a much less traumatic experience. Landmark new recordings such as Konono No.1's amazing Congotronics (who would have guessed that the greatest electronic dance album of the 21st century so far would be recorded using home-made thumb-pianos and recycled car-parts?), Ali Farka Toure's sumptuous Savane, and Amadou & Mariam's multi-platinum breakthrough Dimanche a Bamako all boast their own distinct and stylish 'look'. And the wave of revelatory retrospective compilations making the last few years such a bounteous time for African music consumers set even higher design standards.

Talking (separately) to two of the men responsible - Mark Ainley of Honest Jons and Miles Cleret of Soundway - both make similarly discreet and carefully worded statements to the effect of 'world music people not having much taste in that area'. Alongside kindred spirits Francis Falceto (whose Éthiopiques series has included some of the most remarkable music released in any form over the past decade) and Samy Ben Redjeb (whose Analog Africa label's recent African Scream Contest is the most exuberant funk release of the year so far), these are currently redefining the African canon in the same way that great American song collectors like Harry Smith mapped out the landscape of the blues and folk revivals of the Sixties.

At a time when the idea of the album as something you can hold in your hands is supposed to be on its way out, there is something inspiring about Cleret, Ainley and co's tireless pursuit of the perfect artefact - whether that be a long-lost vinyl single hunted down in the back streets of Accra, or a reissue package crammed so full of visual and musical information that it functions as the perfect antidote to the cultural emptiness of the age of the free Coldplay download.

'These days it's more important than ever to try and make your records things of beauty,' maintains Cleret, whose Nigeria Special selections (see Charlie Gillett, page 66) - with their alluring combination of bright colours and 'pop-arty hand-done Letraset' - replay the exuberance of original Fela Kuti artwork through a distinctly post-punk sensibility.

Ainley, whose ear-opening London is the Place For Me series, and ongoing trawl through the EMI archives of the Twenties, have redefined our understanding of just how far back British pop music's African lineage stretches, illuminates his exquisitely packaged albums with fascinating polemical sleevenotes. 'It shouldn't just be about downloading a couple of songs and letting them blend in with everything else,' he explains. 'The impact music has on you will be so much richer if you make the effort to try and understand where it comes from and what it's trying to say.'

Both Cleret and Ainley have profound objections to the imposition of what the latter calls 'a Western idea of authenticity', which has often been at least the implicit goal of previous generations of African music evangelists.

'I remember the effect hearing James Brown or Jimi Hendrix for the first time had on me,' Cleret explains, 'and why should anyone in Africa be any different? If you're a 21-year-old student with a guitar, why wouldn't 'Sex Machine' or 'Voodoo Chile' have the same impact on someone living in Lagos as someone living in Liverpool? That's what makes music great - the amazing things that happen when people try and copy someone else and get it slightly wrong.'

With its marvellously wonky fusion of American soul and the ancient coronation music of Benin, Cleret's next release - Sir Victor Uwaifo's Guitar Boy Superstar 1970-76 - is a case in point. Talking to the 67-year-old Uwaifo (who is no more a 'real' sir than Duke Ellington was a real Duke) at his home in Benin City in Nigeria, the story of his career casts a damning light on the patronising idea that African music needs to be somehow separated off for its own protection from decadent Western pop.

Far from being the denizen of some exotic anthropological netherworld, Uwaifo inhabits a creative landscape that looks rather familiar. Having first learnt to play the guitar by copying Spanish flamenco records on a home-made instrument made from bicycle spokes and animal traps, he went on to earn Africa's first gold disc for selling over 100,000 copies of his biggest hit, 'Joromi', in the late Sixties. He now lives in a house called 'Superstar Highgate' (come back and try again when you've got a street named after you, Noel Gallagher) on Victor Uwaifo Avenue.

As well as a recording studio, this extensive property has its own hall of fame and chamber of horrors. If a generation of callow indie whippersnappers are about to take Sir Victor Uwaifo as the benchmark of what it means to be a proper rock star, nothing but good can come of it.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire